What Does the Future Look like for Post-COVID Downtowns?

Written by Candace Damon

We have been wondering how the diversity of cities in which we work are innovating and adapting to the new reality of hybrid work. Specifically, we were curious if the civic leaders with whom we’ve worked on downtown revitalization in some parts of the country had lessons to share with their counterparts in other regions. Below, we invite you to read responses from nine private developers, city officials, business improvement district heads, and other civic leaders. Here are the key takeaways:

Fort Lauderdale

Three pillars are driving Downtown Fort Lauderdale’s (FTL) successful evolution: a strong pipeline of residential development; offices that blend the line between living and working; and investments in public space.

More than 6,000 new residents moved to Downtown FTL in the past two years. The population growth—80% since 2010—created a healthy balance of residential and commercial uses. While most city centers largely made up of office buildings went dark during the height of covid, Fort Lauderdale thrived.

Traditional offices in FTL are now competing with unique amenities in new residential developments, from outdoor terraces to dog runs. This healthy competition requires new offices to up their game and blend the line between living and working, which in turn attracts new talent and the companies hiring them to Downtown Fort Lauderdale.

Quality places for the entire community to gather outdoors are key to an equitable future. For example, the reimagining of Huizenga Park in Downtown FTL will transform a vacant large outdoor event space into a highly activated park.

By prioritizing new residential growth, blending the line between living and working, and investing in accessible public spaces, cities can reenergize traditional central business districts towards a more vibrant and resilient future.

Pacific Northwest

Adaptive re-use is one of the most powerful tools we have for revitalizing the public realm and commercial business districts in a post-Covid world. The most immediate action item for local and state government in this new environment is to encourage change in use from older small floor plate office buildings into affordable residential units, close to services and jobs. Small floor plate office buildings can easily be converted to small residential apartment units and Single Room Occupancy (SRO) formats, if regulatory obstacles are removed. In fact, governments should provide subsidies to encourage these conversions through incentives, including low interest loans. We have a housing affordability crisis, and we need to get serious to solve it. This will address affordability and urban vitality at the same time. Single room occupancy should also be encouraged.

Experimental retail in the urban core should also be encouraged. For example, Urban Renaissance Group is currently reimagining Portland’s Lloyd Center — once the largest mall in the world, which “Portlanders had left for dead.” With a new master plan and tenanting strategy, Urban Renaissance Group is proud to engage in this iconic project turning around.

New York City

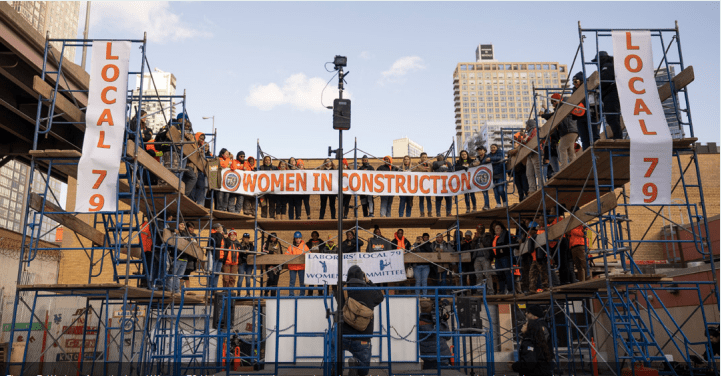

New York City has a rich and beautiful history of adapting and innovating during moments of uncertainty, struggle, and crisis. Case in point, during the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, the city’s people reclaimed their streets as well as the city’s underutilized spaces. While this is nothing new to many New Yorkers, it became a citywide reality, taking on a brand-new energy with people of all ages and economic status demanding—and creating—more spaces for outdoor activities.

People need to be around other people and thanks to these new spaces, New Yorkers were able to truly appreciate the pedestrian-friendly environment. The city quickly adapted several different areas, finding room for outdoor classes, eateries, and more. As with several European cities, the parts of the city that embraced these changes became more vibrant and their stores and restaurants lived to see another month.

Fortunately, city leadership has supported efforts like Open Streets and there is now enough data available to know that an investment in the public realm not only leads to an increase in revenue for local business, but also increases quality of life in a way that people want to return to the reimagined business districts.

Jacksonville, Florida

Like all cities, we’re still adjusting to the “new normal” in Jacksonville, Florida. We as city builders need to continue to focus on what’s important — the people that make our urban centers great. In Jax, we have focused on supporting existing tenants, and adding residents, both valuable and effective strategies.

Still the effects of pandemic were substances. In Downtown and citywide, our office market is experiencing record levels of available and vacant space[1]. However, direct asking rates have not only surpassed pre-Covid levels, but they have actually reached record highs[2]. Talk about a new normal! Downtown covers less than one percent of Jacksonville, but it’s home to a third of Jacksonville’s office inventory and so most affected with changes brought on by increased remote work.

Yet these negative effects from the pandemic are balanced out in Jacksonville by both a huge increase in relocations to North Florida and ongoing diversification of who is coming Downtown. Sustained growth has actually led to an overall increase in street traffic Downtown. Plus, in the past five years, we here in “DTJax” have focused on adding residents and have doubled that number over the past decade. If all the development projects in the current pipeline are built, the number of residents will double again, reaching more than 16,000 people. Meanwhile, the City and our Downtown Investment Authority is investing heavily in waterfront activation, parks, and bike and pedestrian trails to provide unique amenities to enhance the quality of life and recruit business and talent.

Downtown Jacksonville is on the rise! All of these statistics come from our new State of Downtown Jacksonville Report 2022, to be released soon at DTJax.com/research.

[1] 2022 Q2; 26.1% vacancy rate in Downtown, 19.8% in Jacksonville overall

[2] 2022 Q2 Average Lease Rates: $22.96 for Downtown, $21.94 for Jacksonville overall

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

In Philadelphia, office-to-residential conversion is not a new concept. A quarter-century of successful conversions of old office buildings, while new ones have been added, has yielded a highly diversified downtown with one of the country’s largest residential populations. Today, foot traffic on Center City sidewalks is approaching pre-pandemic levels, despite the fact that only 52% of office workers have returned, typically only three days per week. Residents, and increasingly tourists, have animated streets and generated economic activity that has insulated downtown retail and restaurants from a more pronounced downturn. Demand from residents and visitors for parks, shopping, museums, and theater will sustain the amenities that entice more office workers downtown.

A diversified downtown brings together people from across the income and socioeconomic spectrum. Compelling research from Raj Chetty has demonstrated that meaningful cross-class connections boost individual economic mobility more than anything else. As regions become more politically polarized, neighborhoods sort by demographics, and social media displaces eye contact, downtowns remain places where everyone can come together and share space, making downtowns a key accelerant of upward mobility and a pathway to the American Dream.

Chattanooga, Tennessee

What happens when you combine a pandemic with a city that has been voted “Best Outdoor City” twice and offers the world’s fastest community-wide internet through their local municipal utility, EPB? It welcomes a flood of new residents and companies along with recognition as “PC Mag’s 2021 #1 remote-working town.” Since 1986, River City Company has led downtown redevelopment projects, which have been replicated across the United States, including a renowned riverfront featuring large-scale festivals, billions of dollars generated from tourism and a renewed focus on emphasizing creating an atmosphere for residents first.

Today, organizations like River City Company are needed more than ever. As Chattanooga continues to evolve, River City Company serves as the convener and works with companies to transform single-use spaces like offices and surface level parking lots into dynamic spaces geared toward improving social interactions, new housing types and connections to culture. By no means does this mean the “traditional office” is dead. In fact, Steam Logistics, who was just ranked #254 on the Inc. 5000 list of America’s Fastest Growing Companies, is renovating a decades vacant downtown building to welcome 400 employees to their new headquarters.

For those returning to the office, some are expecting more from it. green|spaces just announced embarking upon a “Living Building Challenge” with the goal of a creating a health-conscious community hub that is net positive water and energy. History has shown us that downtowns can be resilient, but only if the residents and businesses are willing to take steps to evolve and transform. Chattanooga, where the streetlights were once set to blink after 5pm, is a shining beacon in the South that has proven through strong private/public partnerships, innovation, adaptiveness, and a bit of grit, you can create a city where all can thrive.

Arlington, Virginia

COVID has changed the landscape for downtowns and central business districts. Locations that foster a mix of uses, welcome inclusive growth, invest in open spaces, provide regulatory flexibility for reuse, and embrace innovation will be best primed to succeed in building a more resilient, competitive, and equitable market.

Seek Balance. The pandemic exposed the economic vulnerabilities of office-dominated downtown districts. In National Landing, a growing downtown and innovation district in Arlington, VA just outside DC, we have learned the importance of a balanced mix of uses — including housing and open space — for a competitive district. Our nearly 1:1 ratio of workers to residents has buoyed the area and fostered a vibrant, active streetscape. Increasing housing, including committed affordable housing and adaptive reuse of vacant space, is key to building an equitable future, especially amid affordability pressures.

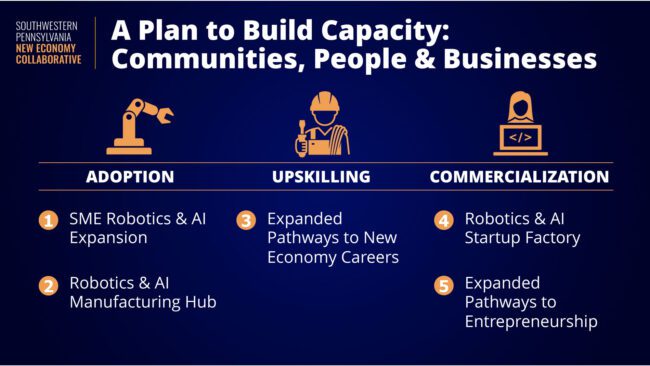

Innovation Mindset. To tackle vacancies/reuse, we are keeping our sights set in National Landing on embracing innovation, digital infrastructure, technological advances, and sustainability as key to evolving our future. We are building on the assets of major employers and educational institutions, like Amazon, Boeing and Virginia Tech, to pilot technology, enhance mobility, and support workforce development to cultivate talent for an inclusive ecosystem.

Vancouver, British Columbia

As a city challenged with extreme issues of affordability, the greatest lesson the Metro Vancouver region stands to take away is to embrace that “traditional” doesn’t look the way it used to, and that this new reality has accelerated a new definition of commercial business districts.

Across the region, Vancouver’s past decade of transit expansion created half a dozen neighborhoods with unique cultural and ethnic identities, each at a scale and mix of uses to rival the traditional commercial business district in downtown Vancouver. Prior to COVID, while many of these neighborhoods built more affordable communities focused on providing housing options, residents still commuted to the traditional commercial business district for jobs and services. All of that that changed after COVID.

This new reality has shifted, so instead of these neighborhoods being miles away from the urban core, they have spread new services, investments, and jobs across this diverse region. It has created a fundamental shift in equity and access across Metro Vancouver that must remain as much as a focus as the reenergizing of our “traditional” commercial business district.